By Greg Quill Entertainment Reporter February 7, 2008

Brian Gladstone started Winterfolk to help his music career. Now he keeps in the background

In its sixth year, Toronto’s annual Winterfolk roots music festival might – just might – make a profit.

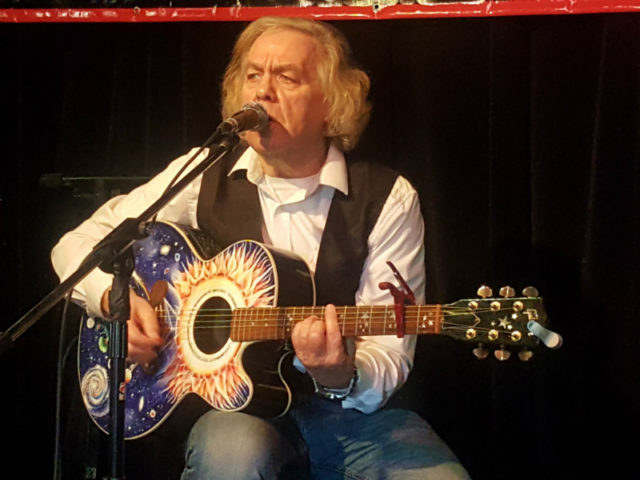

That’s not festival founder and artistic director Brian Gladstone’s biggest concern, but a profitable event means the former research engineer and inventor of power transformers might be able to relax a little, get in a little guitar-picking time.

“For the first four years we lost money, I lost money,” Gladstone says of his creation, the three-day downtown festival that opens again tomorrow night at six venues in the Danforth-Broadview pub strip.

More than 100 performers, including a featured Quebec contingent with Michael Jerome Browne, Notre Dame de Grass Bluegrass Band, Neema, Mike Goudreau & the Boppin’ Blues Band and Les Tireux d’Roches, constitutes a remarkably liberal roster of traditional folk, blues, country and contemporary roots music that has become Winterfolk’s trademark.

In Toronto’s snow-blasted February landscape, the festival is an oasis of conviviality, musical diversity and invigorating warmth. And for the most part, it’s free.

That’s because last year, when government agencies came to the party with a substantial amount of funding, Winterfolk actually broke even on the strength of a couple of ticketed concerts.

“I had to be willing to lose my own money for a few years before the various government agencies considered us worthy of funding,” says Gladstone with a shrug. “Canada Council requires some inter-provincial artistic activity, and then covers the cost of bringing artists to Toronto, paying their fees and accommodation expenses.

“The idea is that the out-of-province acts will be able to book other gigs or build a tour around Winterfolk. Last year we featured artists from New Brunswick. This year it’s Quebec.”

With a subsequent increase in attendance and the chance to produce three ticketed concerts (priced from $5 to $12) this weekend at the Eastminster United Church (310 Danforth Ave.), Gladstone predicts his first small fiscal return in six years.

Winterfolk kicks off tonight with a ticketed concert at the Eastminster venue titled the “The Blues of Winterfolk Unplugged,” featuring Browne in a solo spot, followed by six blues all-stars (Jack de Keyzer, Al Lerman, Tony Quarrington, Maureen Brown, Mr. Rick Z and Suzie Vinnick) performing together as Winterfolk Jug Band.

After subtracting his fee as chief organizer, the festival profits, such as they are, will help fund the Association of Artists for a Better World, a not-for-profit organization Gladstone established five years ago promoting environmental awareness, global peace and the spirit of protest through music. The CDs produced by the organization are handed out free to interested activist groups, corporations and sympathetic radio programmers.

If all that sounds a bit hippy-dippy, Gladstone isn’t fazed. He and his elder brother Howard – who happens to be the producer and artistic director of the annual midsummer Toronto City Roots Festival in the Distillery District – are unashamed folk-era recidivists.

“Howard taught me my first guitar chord … we were at Woodstock together in ’69, the Woodstock,” enthuses Gladstone, 58.

“We grew up in the 1960s. The music of that time shaped my mentality. I really do believe songs can generate funds, ideas, consciousness and hope for a better world. The (Better World) motto is, `We can use our voice to change the world and there’s magic in our words.'”

The brothers have a lot more in common than songwriting, guitar picking and a passion for 1960s folk music. Until Brian quit his job two years ago, he was Howard’s partner in Toronto-based Plitron Manufacturing, building unspeakably complicated transformers that are key components in equipment used in scientific, medical, computer, sound recording and military electronics.

“I was a tech nerd from the age of 12, and worked in cutting-edge research for 25 years,” Gladstone says, flashing a cover-page article in a recent issue of a high-tech electronics magazine extolling the virtues of his latest – and perhaps last – invention, a device that filters a formerly unknown form of electromagnetic pollution from the 150-year-old grids of big-city electrical infrastructures.

“We identified it as a health problem and made the filter … the rest is up to legislators.”

He gave up his not-too-shabby salary and tech-nerd fame – but not the royalties on his and Howard’s patents – to live a dream he has nurtured for most of his life: to become another impoverished, underappreciated folk troubadour in an already overcrowded arena of younger, tougher contenders.

“I was a late starter,” he explains. “I didn’t get into playing music till my late 40s. I was the single parent of three kids, and I had a lot of time on my hands at night to write and practice. I didn’t want to be 80, wondering why I didn’t do this.”

Dismissed at first by official Canadian folkdom as a pop-up festival run by a self-serving wannabe, Winterfolk has earned its scars and survives largely because Gladstone has kept the faith with the artists he has booked over the years, paying them promptly, delivering well-equipped stages and enthusiastic audiences, and running a virtually wrinkle-free event, even when it hurt.

“I got into (Winterfolk) because it was too hard to get booked at other festivals,” says Gladstone, whom some former associates describe as a heavy-handed manipulator and calculating self-promoter. Gladstone doesn’t disagree.

“After 200 rejections, I decided to make my own festival and book myself. It was perhaps not the best reason.”

His lesson learned, Gladstone stays well behind Winterfolk’s curtain these days, watching from the back of rooms, listening to the buzz, wheeling and dealing with venue owners who also contribute a cut of their takings to the festival’s coffers. If he performs, it’s rarely, and usually in the company of other pickers.

“There was a festival void in the city in winter,” he says, “nothing from the end of August until May, and so many performers in town were looking for work. There’s a craving for roots music in Toronto … and Winterfolk seems to be filling the gap.

“It’s good for the economy, good for the musicians, good for the venues, good for the community. It’s a no-brainer.”

For all the details on Winterfolk, go to abetterworld.ca