What in the world does the word folk mean in 2004, LI ROBBINS asks. The answer, my friend, is blowing in the prevailing winds of change.

What in the world does the word folk mean in 2004, LI ROBBINS asks. The answer, my friend, is blowing in the prevailing winds of change.

Includes Interview with Brian Gladstone.

By LI ROBBINS – Saturday, January 31, 2004 –

Other peoples’ parents had cocktail parties. Mine had hootenannies, during which the invocation of the name Pete Seeger made it clear he was closer to God than the Pearly Gates. This was at the height of the folk era, when there were no serious doubts as to the defining characteristics of the various strands of music called folk — commercial Kingston Trio manifestations aside. The ethic of folk was clear. It was old and young enthusiastically singing or marching to protest injustice, or better still, doing both simultaneously. Folk was rousing choruses about overcoming, some day, or about fiercely maintaining your principles and thus preventing your union from being busted.

But then came folk-rock. And singer-songwriters. And finally something called roots music. The comfy gatherings known as folk festivals began, including bands that shocked the faithful by out-Dylan-ing Bob — not only were there electric guitars, there were groups that wouldn’t be amiss in rock clubs. Not to mention aggregations of musicians performing something called "world music." By the 21st century, folk as a recognizable genre would seem to have vanished.

But then came folk-rock. And singer-songwriters. And finally something called roots music. The comfy gatherings known as folk festivals began, including bands that shocked the faithful by out-Dylan-ing Bob — not only were there electric guitars, there were groups that wouldn’t be amiss in rock clubs. Not to mention aggregations of musicians performing something called "world music." By the 21st century, folk as a recognizable genre would seem to have vanished.

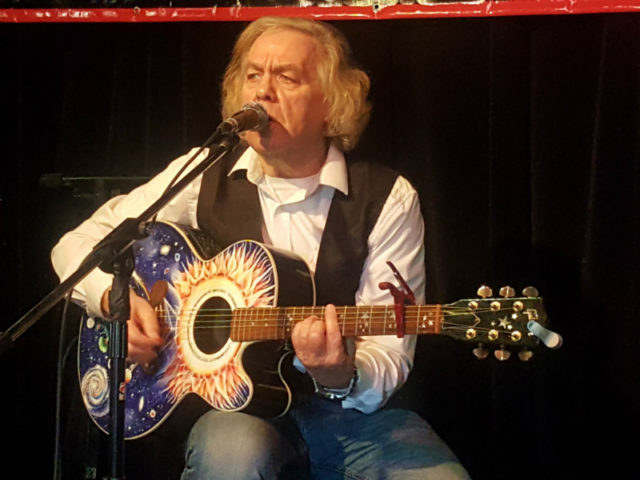

Brian Gladstone, festival director of the 2nd annual Winterfolk, an indoor folk festival held in downtown Toronto (Jan. 30-Feb. 1), doesn’t agree. "The new folk revolution is happening beneath our feet — like the new millennium version of the great roots awakening we saw in the Sixties," Gladstone says.

That said, Gladstone isn’t willing to parse the nuances of folk and related terminology, the singer-songwriters versus roots. Yet Winterfolk’s roster is clearly closer to the original Sixties’ folk proposition — guys and gals with guitars — than it is to any sprawling notion of folk music.

"We wanted to focus on singers who write their own material," says Gladstone. "And on guitar players. We didn’t go the route of bringing in headliners, the way many summer folk festivals do. It’s part of the ethic of this festival — everyone has equal status."

That’s an ethic in keeping with the Sixties’ attitude — "have guitar, will sing protest song." But not in keeping with the prevailing winds of change endorsed by folk music’s largest professional association, the Folk Alliance, based in Silver Spring, Md. One of its key strategic goals is to "change the face of the Folk Alliance," both membership and leadership, in recognition of the "ethnic and cultural diversity of North America." It’s also a recognition of the logic of coalition building with folk music’s closest, equally marginalized cousin — world music.

"The folk world has ebbed and flowed in terms of what the audience looks like, and we want to represent the whole spectrum," says Phyllis Barney, executive director of the Folk Alliance. "Folk music is not a very small box any more."

Barney credits the Canadian branch of the Folk Alliance with forging this new direction, saying that some of the presenters based in Canada, with its acclaimed multicultural make-up, have been "very open and creative." The umbrella American organization has followed suit. This union might seem to only muddy the "what is folk music" waters (and yes, blues is sometimes also included as "folk"), as well as the Folk Alliance’s own goal of "creating a working definition of folk music for media use."

"It’s the "F"-word problem," jokes Barney. "There are so many misconceptions about folk. Everyone seems to have their snapshot — for one person it’s Bob Dylan, for another it’s Bulgarian throat singing, for another it might be bluegrass or Celtic. It’s easier to describe the attributes — it’s music from the community that speaks with universal themes, it’s accessible, people feel comfortable with it, and feel a sense of ownership."

Any hope of reclaiming the "F"-word was probably not abetted by the most recent public kick at the folk can, Christopher Guest’s 2003 mockumentary A Mighty Wind. Although many critics felt the movie was almost too deferential in its treatment of the "commercial" end of folk, the film presented the music as a kitschy souvenir of time and place, not as vibrant, evolving, or even marginally aware of its own fallibilities. It also largely ignored the sorts of artists who were the soul and lifeblood of folk, people such as Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie. Ironically, the latter’s music is one of the most direct conduits to a notion of a folk-music continuum, with Guthrie’s work successfully being performed in ways he never heard in his lifetime — through the alt-country band Wilco with British rocker Billy Bragg, and New York’s radical klezmer band, the Klezmatics, for example.

This fresh view of Guthrie’s work isn’t only because of the compelling stew of whimsy and profound politics found in his songs. It’s also driven by the continuing efforts of the Woody Guthrie Foundation and Archives, directed by Guthrie’s daughter Nora. She’s a passionate voice for her father’s approach to folk. "Woody said, ‘all you can write is what you see’ — his credo for songwriting," Nora Guthrie says. "But maybe today some only see by watching TV, or by only looking at themselves. There are embarrassingly few great folk singers now."

In Nora Guthrie’s take on her father’s vision, folk isn’t about a style of music, a particular language, or electric versus acoustic instrumentation — it’s about truth telling.

"Folk is inherently about social issues, about causes. Folk music has gone out of fashion because it’s very difficult to live that life, to be intelligent enough, strong enough. Although maybe people are doing it in other ways, like Michael Moore in filmmaking." Guthrie adds.

"You have to be willing to lose everything. . . . You might have success, but you can’t be too attached to it. Not if you’re going to speak the truth and say what you see."

It seems unlikely the "F"-word will ever again signal a commonly held understanding of a contemporary genre of music. More likely it will continue to sit uncomfortably alongside "roots" and "singer-songwriter." Perhaps Guthrie’s interpretation of folk as being a way of interpreting life will have more continuing meaning. For as Louis Armstrong once put it: "All music is folk music. I ain’t never heard a horse sing a song."

What in the world does the word folk mean in 2004, LI ROBBINS asks. The answer, my friend, is blowing in the prevailing winds of change.

What in the world does the word folk mean in 2004, LI ROBBINS asks. The answer, my friend, is blowing in the prevailing winds of change. But then came folk-rock. And singer-songwriters. And finally something called roots music. The comfy gatherings known as folk festivals began, including bands that shocked the faithful by out-Dylan-ing Bob — not only were there electric guitars, there were groups that wouldn’t be amiss in rock clubs. Not to mention aggregations of musicians performing something called "world music." By the 21st century, folk as a recognizable genre would seem to have vanished.

But then came folk-rock. And singer-songwriters. And finally something called roots music. The comfy gatherings known as folk festivals began, including bands that shocked the faithful by out-Dylan-ing Bob — not only were there electric guitars, there were groups that wouldn’t be amiss in rock clubs. Not to mention aggregations of musicians performing something called "world music." By the 21st century, folk as a recognizable genre would seem to have vanished.